When Ranga Dias, assistant professor of Mechanical Engineering and Physics and Astronomy, found out that he had been dubbed one of the most 100 influential people in the world, he said he was surprised. Dias had been selected for Time Magazine’s 2021 TIME100 Next list.

“My wife thought that it was a mistake,” Dias said.

Dias and his team at the University have been at the forefront of advancing research on superconductors (materials that can transmit energy without resistance). In October 2020, his team set the record by creating the world’s first room-temperature superconductor. The team combined hydrogen with carbon and sulfur to synthesize a chemical called carbonaceous sulfur hydride in a diamond anvil cell (a device that can create extreme pressures.)

At about 58 degrees Fahrenheit and 267 ± 10 gigapascals (an incredibly high pressure), the carbonaceous sulfur hydride exhibited superconductivity. Previously, superconductors needed incredibly cold temperatures, but Dias and his team discovered a way to bring up the temperature by increasing the pressure.

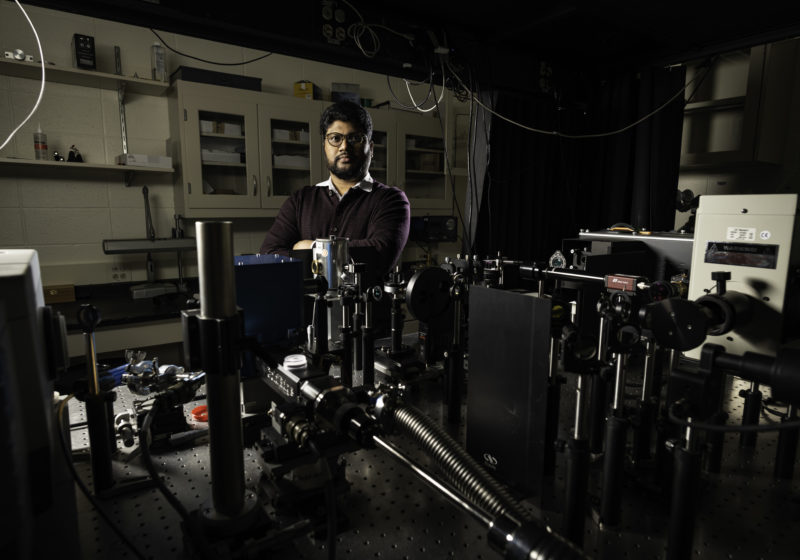

A magnet floats over a superconductor cooled in liquid nitrogen, part of a demonstration set up in the lab of assistant professor of Mechanical Engineering and Physics and Astronomy Ranga Dias in Hopeman Hall on August 26, 2020. Dias is studying the potential and applications of room temperature superconductivity in dense hydrogen-rich materials and carbon-based materials. Courtesy of J. Adam Fenster

The ultimate goal of work like this is to have superconductors work at atmospheric pressure and temperature, which would let them theoretically power things like hoverboards and levitating trains. Currently, the main challenge is the incredibly limited theoretical framework to guide such research.

Superconductors have been around since the beginning of the 20th century and scientists have been working for years to bring them up to room temperature. In the last five years, Dias and his team have advanced that research significantly.

In 2017, Dias was part of a breakthrough on getting pure hydrogen to a metallic state, a vital part of achieving room-temperature superconductors. The research was conducted with Professor Isaac Silvera, Thomas D. Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences, when Dias was a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University. Silvera has been researching condensed matter and physics of particles for more than 45 years.

“Hydrogen is the backbone, the main driving force behind room-temperature superconductivity,” Dias said. “If you just take pure hydrogen, you have to go up to really high pressures like around 500 giga pascal, [which is a] huge amount of pressure.”

The discovery of metallic hydrogen by compressing pure hydrogen with a diamond anvil cell was incredibly helpful.

Finding the ambient pressure of superconductivity, which is around 270-350 kelvin and around 0-10 GPa, is the “holy grail of physics,” according to Dias.

“The challenge is to make it for practical use at atmospheric pressure,” Dias said. “We need to come up with a way to make [superconductors] work at atmospheric pressure and ambient conditions by bringing it from 2.6 million atmospheric pressure to room pressure.”

In addition to the strict environmental conditions needed, superconductors are far too expensive to hold any commercial value. To help lower the cost of superconductors, and to create an economically scalable superconductor, Dias co-founded Unearthly Materials, a start-up company with Ashkan Salamat, a professor at the University of Nevada, who Dias met as a postdoc fellow at Harvard.

When Dias, Salamat, and their team were getting closer to achieving room-temperature superconductivity, they were very skeptical about it at first.

“I didn’t believe it at first,” Dias said. “We decided to do more experiments and not get our hopes too high because we wanted to make sure that what we were seeing was actually real.” It was only after repeated experiments that Dias had what he calls a “eureka moment.”

“It was a strange feeling because while we were excited, we were also surprised,” Dias said. “There was a lot of pause [in the lab] because it was happening after all those years of work.”

Dias, who teaches physics at UR, loves that he can use his own research to explain superconductivity and thermodynamics in class. His students also enjoy having the personal aspect of having a professor teach them about a topic that he has been at the forefront of. It adds an exciting element to class discussions.

Undergraduate students are also a big part of his research, and Dias said he hopes to have them back in his lab once pandemic protocol allows for more people in those spaces.

“I always tend to hire undergraduate students to my lab,” Dias said. “It doesn’t matter if you don’t know much about superconductors but they are always welcome to come watch and participate in the research […] If I can make even one student curious [about superconductors], then I feel really good about it.”

Dias was first introduced to physics and astronomy at the age of seven when he joined an astronomy club in his home country of Sri Lanka, where he was able to meet other people with a passion for the subject. He pointed to his parents, who gave him freedom and support to explore his curiosities. Now, Dias wants to give other young people a similar opportunity at his lab.

And while Dias is very honored to be a part of the TIME100 Next list, his work is just beginning.

“I hope to see hoverboards and magnetic levitating trains within my lifetime,” Dias said.