Every light on this side of the town

In the time of Biblical plague, a great flood was bound to happen.

I woke up on the last day of April to dozens of messages in the WRUR e-board chat, all of them saying more or less the same thing: For the second time in six months, the contractors building the new performing arts place next to Todd had fucked up. The radio station, housed in the basement of Todd Union, was starting to fill with water — again.

We knew this was happening before Facilities called, even though the vast majority of the radio station is weathering coronavirus at home. Two years ago, a former chief engineer — for what seemed like no reason — built a humidity gauging system that sent out blast emails every time station humidity levels spiked unpredictably.

I was a sophomore when this system was first installed, and I thought it was kind of stupid. At a university where this kind of overinvolved, labor-intensive student behavior is commonplace, an unsolicited project of this scale still shocked me. Humidity! Who would ever need to know about that? That’s air water, buddy! It can’t drown you! You can’t even see it!

Despite the gravity of the situation, I couldn’t help but chuckle. There’s always something funny about many people being so mad so early in the morning, and there’s always something funny and absurd about our put-upon little station, where mold has soured an entire recording studio and Public Safety routinely SWATs their way in, imaginary guns drawn, if someone misenters a security code. I laughed at myself for ever doubting the importance of the omnipotent humidity monitor. The laughter lived in my chest and thrummed in a familiar way.

Then, like Dustin Hoffman, Katharine Ross, and Gob Bluth, my smile faded and I just kind of stared off into the middle distance. My last college class ever had been the day before. The great mission, started way back at Oak Street Elementary School in 2003, was accomplished: I was now sufficiently educated, and I didn’t know what to do.

Laura: I really think you should do something about those beautiful poems. They should belong to the world, you know?

Paterson: The world? Well, now you’re trying to scare me.

-“Paterson,” dir. Jim Jarmusch

It was more than a little hypocritical for me to laugh at the humidity thing when I too have long labored at projects that I had to pretend other people cared about. For one thing, I spent three semesters as the Campus Times Humor Editor.

As they say in my line of work, “Ha ha.”

At WRUR I had a Sting (UR’s internet radio) show that averaged four listeners a week. My FM show had a slightly larger audience, members of which would sometimes call in and demand that I play this song by alternative rock band Fountains of Wayne. That would have been fine, except usually my shows sounded more like industrial, post-punk, avant-funk group Cabaret Voltaire.

But my big project, the one I’ve put the most energy into, has to be the Bandcamp page I’ve been running since 2012 (if you’re unfamiliar with Bandcamp, just know that Bandcamp artists are the virgins to the Soundcloud rapper Chads).

For the entirety of high school, I cared about this music project more than anything else. I spent hours working on these songs, recording them, designing cover art, planning release dates for CDs and cassettes — everything. My junior year grades dropped because I was writing lyrics in class instead of taking notes.

But my future didn’t suffer, because I had a plan.

My plan (and my sound, and sometimes even my chord progressions and melodies) was ripped straight from (Sandy) Alex G, a far more successful Bandcamp dude: I would simply release a steady stream of home-recorded and quietly ruminative indie folk albums, build momentum throughout college, then capitalize on a growing audience by becoming a full-time musician at some point around graduation (thus avoiding the need to ever get a real job). It was a brilliant eight-year plan, foolproof in the way any plan made by a 15-year-old is.

Here’s a fun graph showing what the last 8 years have gotten me, monetarily:

There are a few caveats, of course. Most of those 224 downloads were free — if I’d charged full price (and I highly doubt the same number of people would have downloaded my music if they had to pay for it), I would have made roughly 10 times as much money. And my interest in the project waned dramatically after I got to Rochester, where for the first time I was surrounded by people my age who wanted to talk about things besides lacrosse and how funny it would be if we all made fun of the kids in the special education program.

But I still chose to make music a part-time job, where the wage was roughly $12.50 a year. My audience never really grew. I never toured, never even played more than a few shows a year (which, I guess explains the meager salary). But I continued to labor, well aware of my total obscurity and insignificance, as though the entire world was awaiting my next album. Pretending I had an audience made the experience more fun, and it gave me criteria that I had to work to meet; my music had to, hypothetically, entertain an audience, so I actually had to write good songs.

Part of me also thought: What if this started working? What if people suddenly got really into my music and were buying it and sharing it and asking me to come play in their basements and sleep in their attics? Wouldn’t it suck if I didn’t have the infrastructure ready to make that happen? Wouldn’t I be doing the good indie kids of towns like Youngstown, OH and Missoula, MT a great disservice?

It never happened, but at the time, it just hadn’t happened… yet. And as long as something has yet to happen, you have to pretend that it might, which is the same as pretending that it already has.

“I will forevermore, I expect, be trying to re-create the purity of that time. Having done nothing, I had nothing to lose. Having made a happy life without having achieved anything at all artistically, I found that any artistic achievement was a bonus. Having finally conceded that I wasn’t a prodigy after all, I had the total artistic freedom that is afforded only to the beginner, the doofus, the aspirant.”

-“Preface to Civlwarland in Bad Decline,” George Saunders

I was lucky to have a college experience that wasn’t all plotting and preparing and imagining — do too much of that, and you end up living in and for a future that does not and will never exist.

I’ve had some good times, and considering that this is a Big Damn College Retrospective article, I’m entitled to run my highlight reel.

But any amateur nostalgist can pick out great individual moments from their college years. As a champion of melancholy reflection, what I really love doing is picking out great stretches of time.

At the end of sophomore year, for instance, I stayed after finals for senior week. I went to minor league baseball games and to parties that sprouted from midday beer miles, and every morning I ate eggs on an illegal Phase hot plate with 15 of the best friends I’ll ever have.

And the week before this past Thanksgiving, I went on an extremely short-notice roadtrip to Louisville, where I watched those same friends race at cross-country DIII Nationals. On that trip I met a Hobby Lobby worker who reminded me of my mom and asked if I “was there for that 9/11.” I saw both sides of the infamous I-71 “HELL IS REAL” billboard. I saw America.

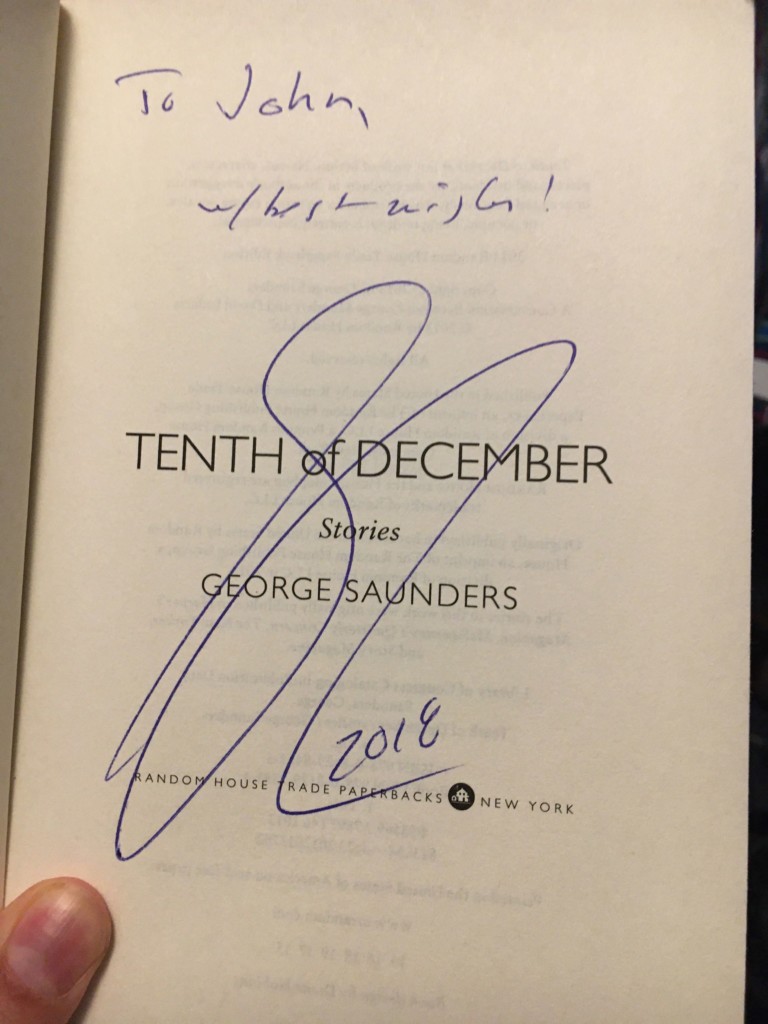

Best of all was the stretch of time bookended by December 5 and December 14, 2018. On the 12th — my 21st birthday — two guys gave me $20 for helping them push their car out of a snowbank by Mount Hope Diner, cash I then immediately spent on tequila at Fort Hill. On the 14th, I went down to Brooklyn for the first Duster show in almost 20 years. But the 5th was special, because on the 5th I went to see the master.

George Saunders is the kind of writer where the very first time you read him, you love him and understand why everyone else loves him, too. Instead of me explaining the post-Vonnegut, late-capitalist appeal of Saunders, just read the second paragraph of his short story Al Roosten.

He also wrote the majority of his first book, “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline,” while working just down the road at Corporate Woods, so, y’know. That’s neat.

Saunders has long presided over the MFA (grad school for creative writing) program over at Syracuse, and he was chosen as the final reader for the program’s Fall 2018 reading series. With the blessing of a professor who would go on to be my advisor, I skipped class to take Amtrak an hour east. Classic anxiety-fueled hijinks followed, such as: getting intimidated by the unique ordering system at Pastabilities and running for the safety of a nearby record store, then returning an hour later when my hunger made me dizzy; realizing halfway through a student Q&A that I, a non-Syracuse student, was very much not supposed to be there and having to edit my hyper-specific question about tense use in the first story Saunders ever published into something a little more basic, so as to avoid detection; booking a return ticket for a train that left long after the reading ended and having to sneak into Syracuse’s private, swipe-locked library, where I camped out for three hours.

It was one of the best days of my life, because I couldn’t have imagined a moment of it happening as it did. This was the anti-laboring-for-future-recognition — this was immediacy.

But really, these two kinds of experiences go hand in hand. Yes, if you just sit back sometimes and let life take you where it will, then you will be amazed at the beautiful and strange shores you can wash up on, how sweet the fruit growing there can be. These little bits of freedom will also remind you of the reason you can spend so much time toiling on those passion projects: There are still no stakes. Like Saunders said, you are still “the beginner, the aspirant, the doofus.” You’re free to mold your time into something just for you and your future, and you’re free to let your time mold you into something both wonderful and strange.

There won’t be any more times just like that. Not at Rochester, not for me.

Henry Hill: And now it’s all over.

-Goodfellas, dir. Martin Scorsese

Well put, Henry.

Why is it all ending this way? Partly because of the unavoidable chaos of disease, and partly because of the inevitable march of time (I was going to graduate in May with or without a pandemic). I still can’t help but feel, however, that the cruel circumstances of this moment are in part due to people looking at pandemic containment responses the way I once viewed the WRUR humidity monitoring system (Yes! It all does come full circle! Viruses are just in the air, buddy! You can’t even see them!)

Remember: As long as something has yet to happen, you have to pretend that it might, which is the same as pretending that it already has.

So here we are. It’s later in the day on April 30. I’m checking back in on the flooding situation. Our chief engineer is living just off-campus, and he’s able to swing by and confirm that, thank God, the flooding is under control and nothing is damaged. Then he sends this picture of our FM studio:

Lots of people have already expressed that anything from before March feels like it happened an eternity ago, so it would be understandable if you have already forgotten that weird meme where people were standing up brooms on their bristles. We did it a lot at WRUR: broom standing in the CD library, broom standing in the conference room. Broom, somehow, after 47 days (we counted), still standing in the FM studio.

After in-person classes were cancelled but before the dorms were purged, a few DJs did a special, farewell Sting show. They played this song; they made merry and eulogized. They stood a broom up in FM, where it kept vigil over widely-despised and oft-malfunctioning radio programming software, and a soundboard with breaking knobs and gummed-up sliders.

Be sure to sweep up on your way out, I guess.

You can labor on things and tell yourself that people will appreciate them later, when time has given everything full context. Or you can just labor on things because you’re alive and you like to spend your time that way. The result, either way, is the same: You leave behind a few strange and beautiful fossils, and in the vast inevitability of time, someone else stumbles across them later and breathes life over them. They find the broom still standing up.

A farewell transmission. Nothing but long dark blues up ahead. But listen: The broom is still standing. Long dark blues. The broom is still standing. Listen.