Graduation is a time for a great many things, when entire families, living and dead, all congregate to try and pick their child out of the thousand of identically dressed yet distinguished students awaiting their degree. In this time of overwhelming significance, students should be particularly attentive to detail, as a way of telling their parents “thank you for selling your kidneys to pay for my political science degree.” This is especially true with graduation attire, as proper etiquette is imperative when dealing with the cap and gown. The cap, for example, is to be worn flat on the head, with the tassel draped off the right side. Upon matriculation, the tassel should be switched over to your left side, as a showcase of the skills acquired during college. Of course, in so doing, you may wonder “why am I moving a colored piece of yarn across my hat?” If so, rest assured that the colorful history of the cap-n-gown is an illustrious one. I know this because now that college is finally over, I finally started doing some research.The origin of the gown dates back to the 12th and 13th centuries when, despite having used a central vacuum system for years, Middle Ages Clerics failed to apply the principle to heat. Subsequently finding themselves in rather arctic abbeys, they turned to full-length gowns to keep themselves warm, and now we, in Rochester, are wearing our gowns during the only non-polar three hours of the year. With clerics responsible for the formation of the first universities, it became customary for many students to take religious vows upon entering college – a practice that, incidentally, ended with the founding of the first fraternity. Nevertheless, with the religious affiliation came religious attire, and that means robes and silly hats. This tradition continued until the questionably accurate year of 1321 when, as the legend goes, Portugal’s University of Coimbra decided to require that all doctors, bachelors and licentiates – those students that mastered the mysterious art of licentiating – were to wear gowns. Understandably, the licentiates were infuriated. Once the idea of non-clerical gowning was adopted by Coimbra, the practice caught on like the plague. Just a century later, fourteenth century universities such as Oxford and Cambridge became so frustrated with some scholars’ excessive clothing – full plates of armor, baggy jeans and the like – that gowns became part the universities’ dress code. Over the next few centuries, graduation grab underwent a number of slight changes. The “tuft” that adorned a typical cap was replaced with a tassel, and the round crown-esque base morphed into some manner of flimsy cardboard, a development that required the invention of cardboard.The respective color of a graduate’s attire came to hold a particular meaning, as well. Though the advent of assigning color significance to academic attire was in Europe in the 1800s, the United States was the first country to standardize it when they decreed that the color “white” was to be worn by anyone successful. Still, to one man, the alluring world of graduation gown coloration was ripe for revolution. It’s hard to imagine what life was like back in the nineteenth century, before the colors associated with graduation were standardized. One can only imagine a dark, foreboding time, when men cried in the streets as they pondered the ambiguous meaning of their tope-colored tassel. All we know about this evil era is that it was apparently too much for the world-shattering Gardner Cotrell Leonard to bear.Finally, six years after coordinating the attire for his own Williams College graduation, Leonard wrote a pivotal article on the future of academic gowns in America. Strangely, Leonard’s father quickly severed ties. With the article affording him a substantial amount of gown-and-tassel influence, Leonard slyly used his newfound power to mold the industry and realize his vision. He gathered with other notables in the field under the banner of the “Intercollegiate Commission,” and much like Coimbra before them, the commish instituted a hierarchy of academic distinction. For each of the respective levels – as well as within each level – Leonard’s group, presumably during lonely Friday and Saturday nights, assigned a color coding to each degree – a development for which those males with a B.A. in music and accordingly pink tassel on their head are doubtlessly grateful. The color code has since undergone a number of changes, most recently in 1986, when the color for a Ph.D in philosophy was changed to blue, so as to more accurately represent the mood of such scholars. With that slight modification out of the way, it would seem that the tassel coding has reached the pinnacle of graduation attire coloration.Yet, as is so often the case with history, none of this information is particularly important. I provided it on the outside chance that you may, one day, find yourself sitting among the aggregate of academics with whom you’ve spent the past four-to-eight years, admiring the galaxy of black and vibrant tassels, like streaking celestial bodies in the darkness, whatever the hell that means, and wondering, “what happened to my collegiate career?” “what does the world have in store for me?” and “what the hell is a health and society major, anyway?” But no longer must you ask, “why am I wearing a cheap black gown and flat-topped helmet with a mauve string hanging in my face?” because now you know.And knowing is half the tassel.Janowitz can be reached at njanowitz@campustimes.org.

femininity

A reality in fiction: the problem of representation

Oftentimes, rather than embracing femininity as part of who they are, these characters only retain traditionally masculine traits.

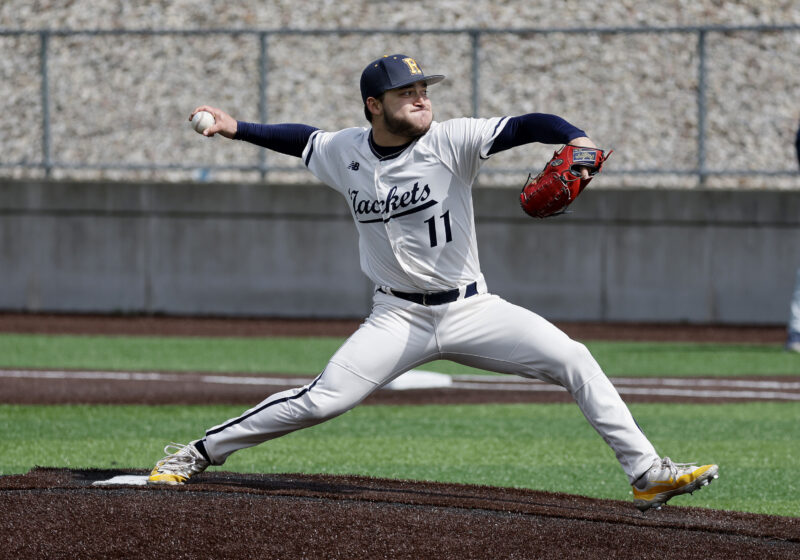

Baseball

UR Baseball beats Hamilton and RIT

Yellowjackets baseball beat Hamilton College on Tuesday and RIT on Friday to the scores of 11–4 and 7–4, respectively.

Administration

Recording shows University statement inaccurate about Gaza encampment meeting

The Campus Times obtained a recording of the April 24 meeting between Gaza solidarity encampment protesters and administrators. A look inside the discussions.