In 2007, the Supreme Court declared greenhouse gases “air pollutants” under the Clean Air Act. That meant the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had a simple question to answer: Do these gases endanger public health or welfare? After review and public comment, the EPA said yes in 2009. That decision, called the Endangerment Finding, covered six gases: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons, and sulfur hexafluoride.

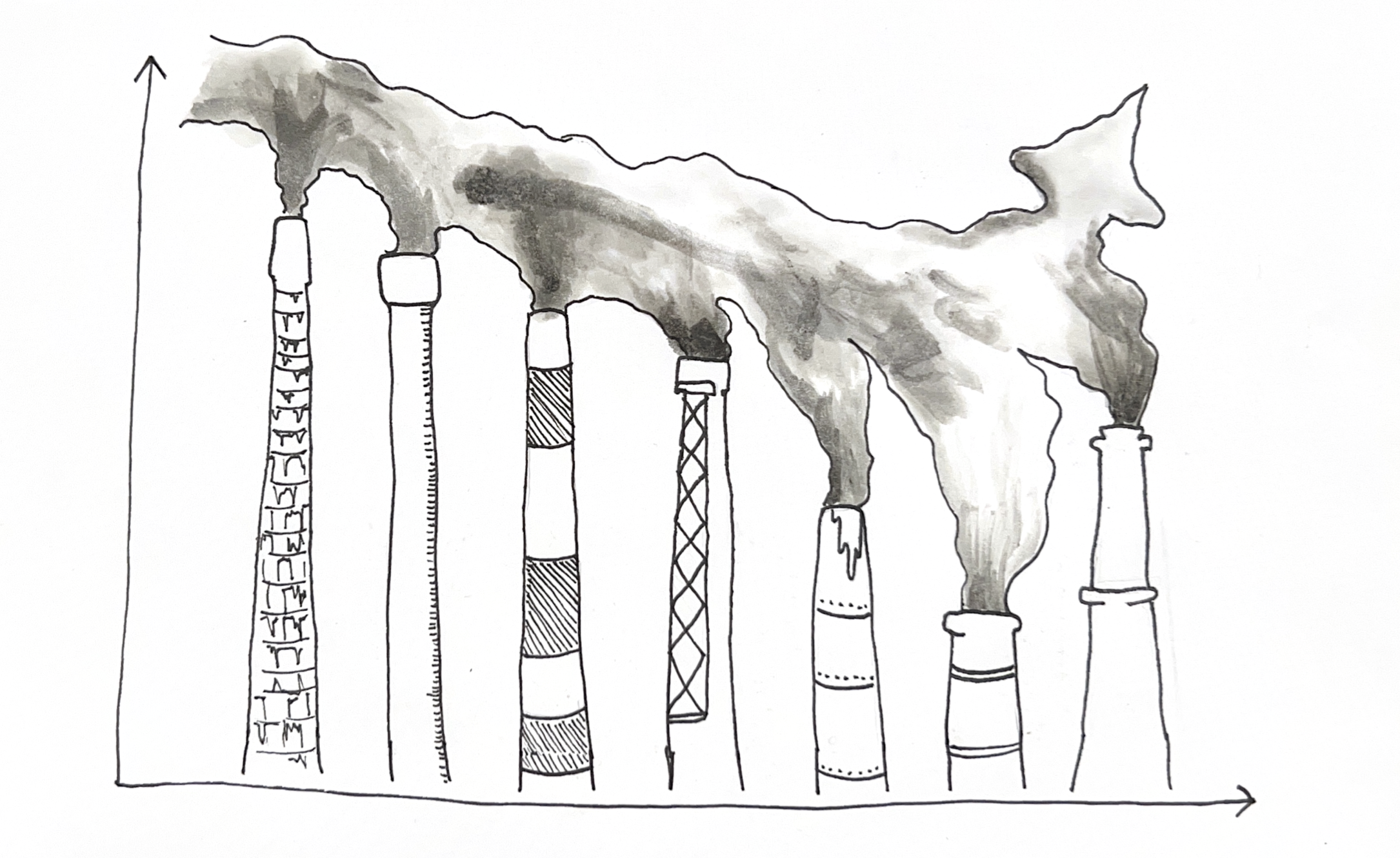

The Endangerment Finding exists because the law is clear: If a pollutant endangers health or welfare, the EPA must act. The evidence shows that rising greenhouse gases increase heat risk, worsen air quality, and contribute to rising sea levels and changing water and wildfire patterns. The EPA received hundreds of thousands of comments before it made the call. Their report did not designate any one climate plan — it did something simpler. It turned on the legal light switch that lets the EPA set limits where the Clean Air Act applies, starting with new motor vehicles.

The result was positive for the environment and for people, and we can point to concrete wins. After the finding, EPA and the Department of Transportation set greenhouse-gas standards for cars and light trucks, which cut carbon footprints and saved drivers’ fuel money at the same time. New rules adopted in 2024 for 2027–2032 built on this, with large net benefits and big projected carbon cuts. The pattern is clear: Set a fair standard, have the industry meet it, and the air gets cleaner. The Endangerment Finding also placed limits on heavy-duty trucks and greenhouse gases within the permit system for big, new, or modified sources. Courts later narrowed some parts of that system, but in short, the Endangerment Finding let the EPA use tools it already had to manage existing risks. It did not invent new laws; it applied an old law to a new pollutant class.

When it comes to the practical protection that the EPA offers in real life, look locally. Car and truck standards reduce tailpipe CO2, lessen the amount of fuel burned, and also reduce co-pollutants that form ozone (O3) and fine particles. This helps everyone, especially those most vulnerable to harm. Fleet-wide fuel savings also help households and small firms. The EPA’s 2024 vehicle rule alone projects large net benefits to society, to the order of tens of billions of dollars yearly, and billions of tons of CO2 avoided long-term — concrete, trackable numbers, not slogans.

Now, the bad news. In July 2025, the EPA proposed rescinding the Endangerment Finding and ending federal greenhouse gas limits reliant on it. The docket is open for public comment under the proposed rule Reconsideration of 2009 Endangerment Finding and Greenhouse Gas Vehicle Standards. If that proposal is finalized, the EPA would no longer have the authority to set pollution standards for vehicles or other sources under key parts of the Clean Air Act. Legal fights would follow, but the aim is clear: Prevent the EPA from acting.

The stated reason is that the agency now argues the science is too uncertain and that Congress, not the EPA, should make decisions on greenhouse gases. In effect, the proposal is framed as narrowing EPA’s role and shifting power back to lawmakers.

This push is tied to the Supreme Court’s 2024 decision ending Chevron deference, which removed the rule that courts defer to agency readings of unclear laws. Without Chevron, EPA can say its past basis for action is less secure, and it is using that shift to justify repeal.

Why is rescission a bad idea?

It breaks a working system. The Clean Air Act uses a well-established process that has already been used to limit countless pollutants. Removing greenhouse gases from this list of regulated pollutants allows climate change and air pollution to continue unfettered.

If the EPA says greenhouse gases do not endanger health or welfare, it cannot use core Clean Air Act tools for addressing climate risk. There is no replacement authority on the table. The result is a vacuum.

It raises costs for families and firms. Rolling back vehicle standards throws away fuel savings and slows innovation that was already under way.

Rescinding the Endangerment Finding ignores newer, stronger science. The scientific record has grown since the EPA made the finding. Leading science groups say the evidence that greenhouse gases harm health and welfare is now clearer than ever.

What could happen if rescission goes through?

There would be no federal tailpipe greenhouse-gas standards. That means fewer guardrails on the nation’s biggest source of CO2 and less pressure to deploy the best low-emission options. Some states would try to fill gaps, but a patchwork is not a plan. The result is more carbon in the air, more climate risk, and more health costs for families.

There would also be stalled or weaker rules for large sources. Courts may allow some limits to stand, but the core legal basis would be gone. New plants and major upgrades could face fewer greenhouse-gas checks, even when low-cost alternatives exist.

Data and transparency are at risk.

The same rollback wave also targets mandatory greenhouse-gas reporting by large polluters. If we stop accurately recording the problem, it only gets harder to address.

We would see more political whiplash. If one White House turns the Endangerment Finding off and the next tries to turn it back on, business planning gets harder. That helps no one.

Some say rescission is needed because climate regulations are costly. But the Clean Air Act has always weighed costs. The EPA sets standards, industries choose how to meet them, and over time, innovation makes compliance cheaper. That is what happened with cars after 2012. It is how we cut sulfur and soot. It is how we cut lead. This is basic economics.

Others say climate policy should come only from Congress. Congress already spoke when it wrote the Clean Air Act and left a broad definition of “air pollutant.” The Court confirmed that greenhouse gases fit that definition. The Endangerment Finding followed every legal process and faced extensive review. If Congress wants to give the EPA more precise tools, great. Until then, the law we have should not be hollowed out.

The Endangerment Finding is not perfect, and it is not the whole answer, but it is the floor we stand on. Pulling that floor out now would not make the risk go away. It would just take away our grip on it. Keep the Endangerment Finding. Keep the tools. Keep measuring, managing, and checking our progress. That is how we protect our environment, and the hundreds of millions who live in it.