Successful researchers will agree that resilience is essential for survival in academia. The failure rate is extremely high — most experiments, grant proposals, and projects will end in disappointment. Resilience is difficult to teach, but it can be built from experience. Taylar Mouton, a senior molecular genetics major at UR, draws upon her resilience to succeed in the lab, as well as to combat racial and gender prejudice facing her peers.

Representation is one privilege many take for granted, and goes hand-in-hand with having strong role models and heroes to emulate. “Having mentors who look like you helps you assess what’s best for you,” Mouton said. “If there’s no representation, you have nothing to latch on to. [As a black woman], I’m doubly at a disadvantage.”

Underrepresentation of black professors and principle investigators (lab heads) can discourage black STEM students from pursuing such careers. “The biology department is decently sized, but I can’t think of any person of color who is a biology professor,” Mouton said. “I come to campus and only see white people in positions of power.”

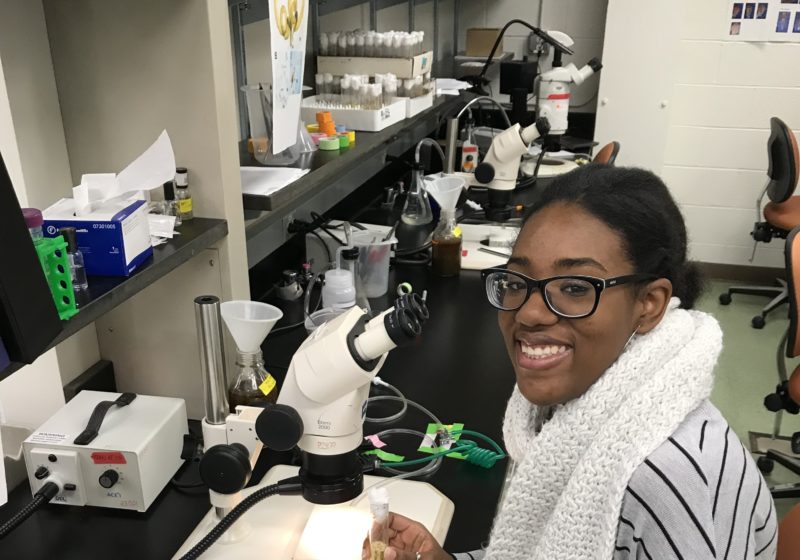

Still, Mouton has stayed on track toward a career in academia. She is studying evolutionary dynamics of the fruit fly genome, working with Dr. Amanda Larracuente in the biology department. Dr. Larracuente has made Mouton’s research experience valuable and enjoyable. “She seems to effortlessly know everything about Drosophila and everything about sequencing and programming,” said Mouton. “She’s willing to make herself available to her students, and tries to fit everyone into her schedule… She made me feel welcomed.”

“Taylar is fantastic to have in the lab,” Dr. Larracuente said. “We love having her.”

The Larracuente lab is interested in the “dark regions” of genomes: DNA sequences we know little about, but which play essential roles in genome evolution and stability. Larracuente and Mouton use a combination of computational biology and wet-lab benchwork to interrogate the fruit fly genome.

However, these “dark regions” are elusive and difficult to study — their exact structure and sequence have yet to be defined, making it challenging to study their function. Mouton initially tried to characterize a particular gene family in flies, focusing on a unique form of the gene that may play a role in fruit fly male fertility. She was able to generate preliminary data suggesting that this was localized to the nucleus, but the project hit a technical wall soon after. “It didn’t go anywhere, so we went back to the drawing board,” Mouton said.

In research and beyond, the most important problems are often the most difficult to solve. As a black woman at a predominantly white institution, Mouton is no stranger to meeting challenge with resilience. UR has made strides towards diversity and inclusion, but work remains to be done, Mouton said. “You start finding things that aren’t being addressed, even if other people recognize it as a problem.”

An academic path is demanding, from laborious coursework to growing pains of starting independent research. With these challenges come inevitable moments of failure, and it’s the response to failure that can make or break a career. Unfortunately, Mouton said, failure can be more discouraging for students of color at a predominantly white institution. Black students may feel chronic pressure to prove their competence because their professors and peers expect them to fail. Even small under-performances can reinforce this often subconscious expectation. Implicit bias is a pervasive barrier to underrepresented demographics in academia. “Most white people don’t realize that they have some racist biases until they’re forced to confront it,” she said.

Mouton experienced this during her first two years at UR. “I was surrounded by so many white faces who I thought were doing better than me,” she said. “Imposter syndrome happens to everyone, but I think it happens more to people of color. Sometimes I’d think, ‘Maybe they’re all right, maybe I’m not supposed to be here.’”

Last year, Mouton fought to establish the Womanist club on campus, a term coined by activist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Alice Walker to represent feminists of color. Mouton’s efforts to create this space were originally met with resistance and a lack of understanding from administration. Finally, after much debate, the club was granted recognition last spring. “I wanted other women of color to have somewhere to go, to have a group that would always be about them,” Mouton said.

Though she has proved to be a passionate and effective spokesperson for students facing these issues, Mouton doesn’t enjoy being in the spotlight. She feels a responsibility to embrace her discomfort for the sake of positive change. “It’s a moment of being uncomfortable,” she said. “I’m doing it for those that come after me.”

Importantly, increasing diversity benefits scientific discovery. The approach that scientists bring to scientific problems is influenced by their unique agencies, and limiting the diversity of scientists limits the diversity of scientific thought. “Why would you limit yourself to the same type of brain power?” Mouton said. “Bring in new minds, that’s how innovation happens.”

Mouton’s story is one of success through resilience. She has made her own confidence and continues to persist through challenges many non-minority students at UR aren’t even aware of. In her future career as a scientist, Mouton wants to make it easier for black students to succeed through active representation. “Having diversity helps bring other people of color into those fields,” she said. “It opens more doors for later generations.”