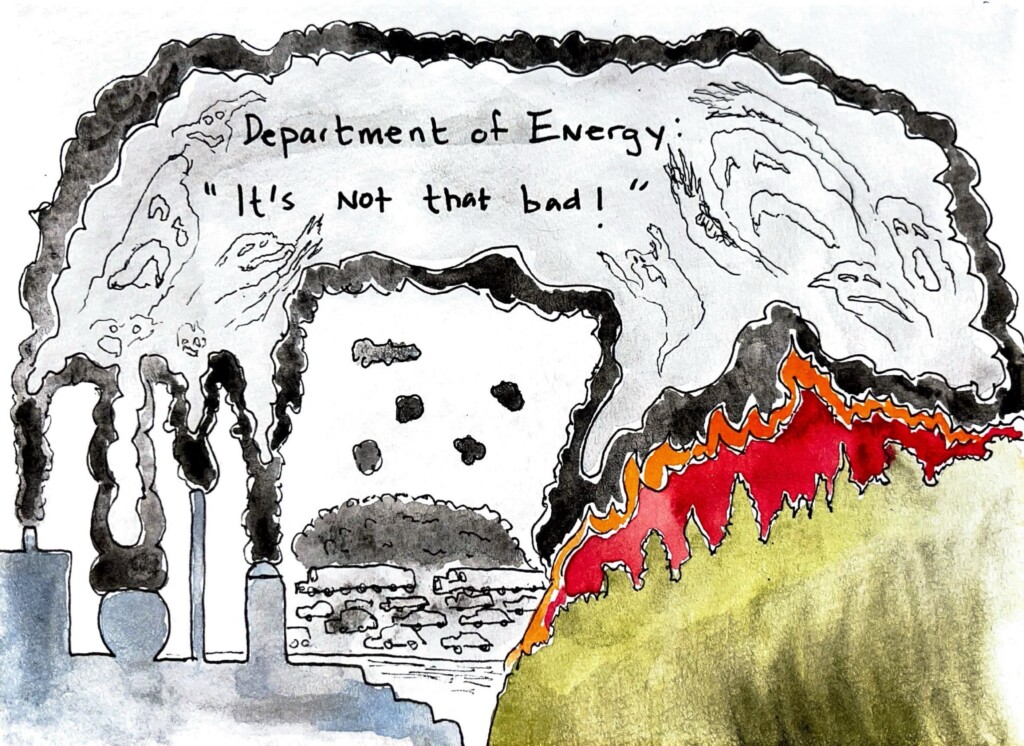

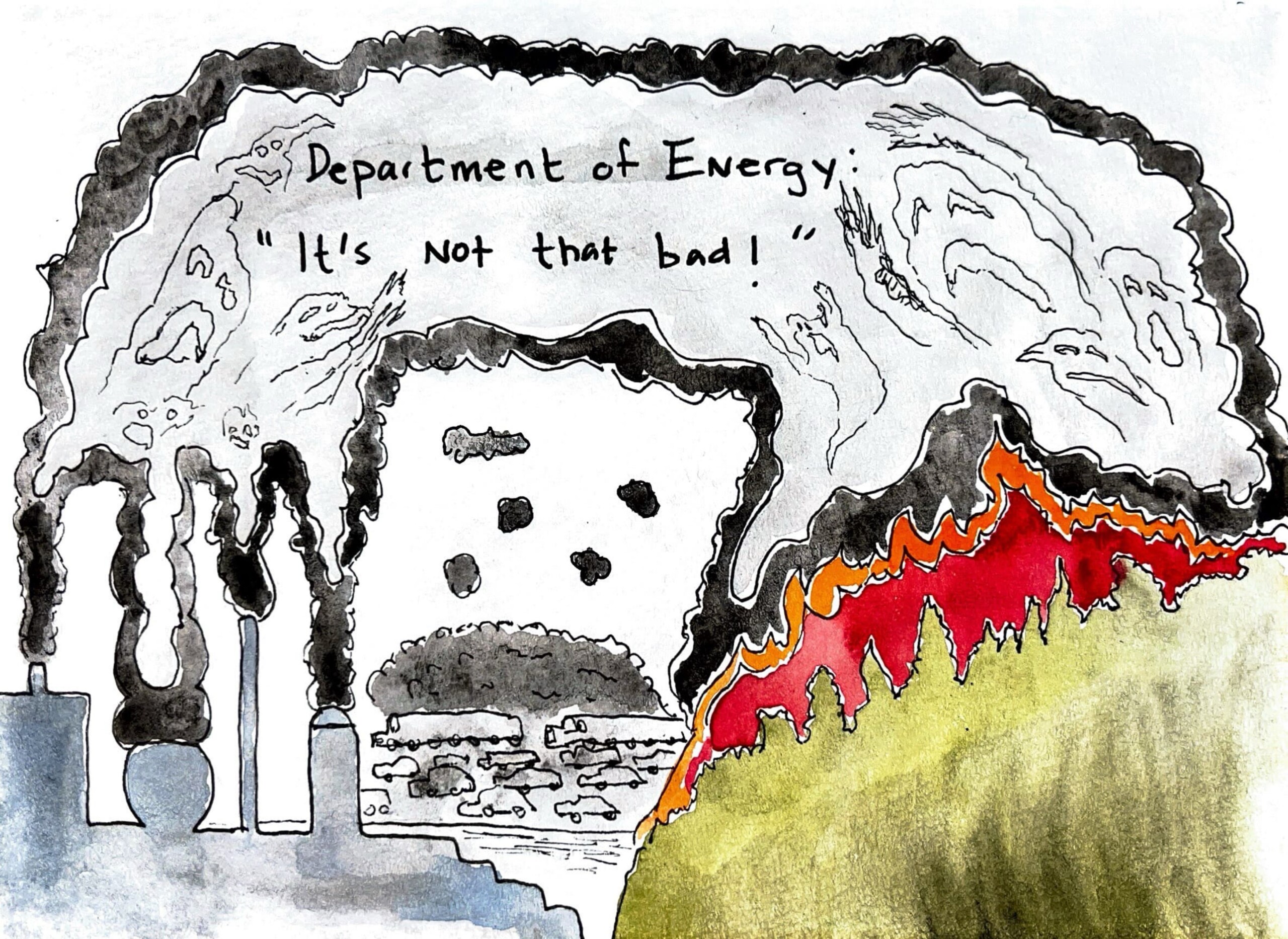

The Department of Energy released a draft report on greenhouse gases and the U.S. climate this July. Downplaying the extent to which humans are warming the planet, and questioning the links between global warming and extreme weather, the report argues that U.S. policy will trivially affect the climate and that aggressive cuts could do more harm than good. In the weeks that followed the report’s release, climate researchers and national security leaders submitted lengthy, detailed responses. Their message was simple: The report gets the science, the risks, and the policy math wrong.

Let’s start with crops. The report begins by stating that extra carbon dioxide can help plants grow. While that is true in a lab, it is not the whole story in a farmer’s field. Heatwaves, droughts, and shifts in rainfall can erase gains from higher CO2 levels. Any honest review must weigh CO2’s benefits against heat stress, water stress, and the emergence of new pests. The experts’ comments note that the DOE draft does not do that.

Next, let us consider cause and effect. The draft argues that humans play a relatively minor role in current warming, and hints that biased measurements are to blame for studies that claim otherwise. The draft also tries to cast doubt on scientifically proven warming signals, with multiple, independent records showing worrying changes in ocean heat levels and land ice cover. The best evidence still suggests that human emissions are the primary driver. That is why every major assessment, from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to the U.S. National Climate Assessment, attributes the most recent warming to human activity. The scientist review of the DOE draft — more than 400 pages from more than 85 experts — lays this out in patient detail.

On the extremes, the draft states that U.S. records do not support increases in heat waves, heavy rainfall, droughts, hurricanes, or wildfires. Here again, the reply from climate experts is direct: the literature shows clear increases in many of these risks, with regional differences, and the DOE draft quotes the records selectively or out of context. Examining the compound extremes that strain real systems — heat combined with drought on crops, heat combined with humidity on worker health, extreme rain on aging storm drains, and wildfire smoke on cities far from the burn — reveals that we are on track for a warmer baseline climate, which will lead to more crop losses, more lost work hours, more urban flood damage, and more smoke-related health burdens.

On policy, the draft makes two claims: first, that deep cuts to emissions reductions could cost more than they save; and second, that even if the U.S. cuts emissions reductions, the change in global temperature would be “undetectably small” for a long time. This first claim rests on using optimistic cost assumptions for fossil fuels and pessimistic ones for clean options, unfairly minimizing the difference between them — all while overlooking co-benefits such as cleaner air and reduced heat-related deaths. Economists and policy analysts flagged this in their responses, including a detailed rebuttal of the draft’s economic sections from the Institute for Policy Integrity at NYU. Meanwhile, the second claim diminishes the impact of the U.S. on global affairs by treating the nation’s policy as if it happens in a vacuum. It overlooks the fact that our actions shape global markets, standards, and policies in other countries, and it omits the fundamental fact that the U.S. has been responsible for roughly a fifth of historical CO2 emissions since 1750.

Climate change and its environmental effects have more impacts than some might imagine. A group of retired generals, admirals, intelligence officials, and defense scholars warned that the draft treats climate risk as an accounting error rather than a stress on bases, supply chains, and fragile states. They argue that downplaying risk encourages delay, which raises costs and leaves the U.S. less ready for economic and operational shocks. In their words, the report is not fit for national security planning. That judgment matters because planners do not get to pick a single “best case.” They prepare for plausible risk ranges and worst-case events.

Part of the reason behind the widespread disagreement toward the DOE’s draft is that it did not go through outside peer review. That’s not illegal, but it’s also not wise for a document aimed at resetting climate risk and, by extension, the EPA’s authority to act. Within days, scientists, economists, state attorneys general, and NGOs submitted comments that walked through errors, gaps, and misreadings in the report. Newsrooms and fact-checkers did the same. These rebuttals are lengthy because the report’s claims are broad. However, the core issue is simple: a shortcut on climate science is a dead end for policy.

So what should readers take from a fight like this?

First, the basics still stand: Greenhouse gases trap heat, and more heat increases the base risks for extreme weather events. Cutting emissions lowers those risks, and acting sooner is cheaper than acting late. Second, precision matters. It is fair to debate the size of each risk and the pace of change, but the debate must stick to complete records and full-cost accounting. Third, our institutions need process discipline. Big claims should undergo external review before they inform national rulings.

As a simple way to think about costs and choices, think of home insurance. We insure our homes not because we think they’ll catch fire, but because the loss if they did is massive enough to justify preparing for the worst. Beyond insurance, we also pay to maintain the state of our homes month to month and year to year. Climate policy follows the same logic on a national scale. Cutting emissions is like insurance, shrinking the likelihood and the scale of losses we cannot afford. But we also prepare for heat, fires, floods, and storms that we cannot avoid. None of this requires panic. But it does require clear-eyed math, steady rules, and a respect for evidence.

What can Congress and federal agencies do now? Keep the EPA’s policies tied to the best available evidence. Direct DOE funding toward energy research and risk-reducing infrastructure, not reports that re-argue settled basics. Build rules on shared federal resources like the National Climate Assessment and other federal climate data systems. These public goods help everyone make better choices and lower costs over time.

What can the rest of us do? Read the whole report, not just a headline. Ask simple questions when you see a bold claim: does it match multiple independent datasets; does it square with trends you can see in heat days, flood insurance losses, crop yields, and wildfire smoke; does it add up when you include health and energy savings? And support local steps that reduce risk now — such as cooling centers, flood maps and drainage systems, grid upgrades, and methane leak fixes — while we push for larger national initiatives. These are not partisan steps. They are the work of basic risk management.

Climate policy will always involve cost tradeoffs. However, we should not tilt the scale by ignoring evidence or skipping review. The DOE draft tried to do both. The response from scientists, economists, and national security leaders shows why that is a mistake. We can argue about pace and tools. We should not argue away facts.

If we want rules that last and investments that pay off, we need to keep the science plain and the process clean. That is how we protect people, save money, and keep our footing in a warming world.