Since the summer of 2018, when Greta Thunberg staged her first school strike for climate outside the Swedish parliament, youth have become one of the leading voices of the climate movement. In just two years, the “Greta generation” has staged strikes millions strong, convinced colleges and cities to adopt green energy, and effectively lobbied elected officials to move climate to the forefront of their political agendas.

Yet, as of April 2019 — the most recent data on record — an NPR poll revealed that just 42% of teachers incorporate climate education into their lessons, and only 45% of parents talk about this pressing issue with their children. Inconsistent with this statistic, the poll also indicates most teachers and parents on both sides of the political aisle agree that climate change should be discussed.

As a young activist who was first meaningfully exposed to climate change in a high school classroom, I’ve had a front row seat in witnessing the power that education can have in sparking one’s passion to act. This topic wasn’t discussed in depth in my home or in any of my other classes, but when I was finally exposed to it, I knew I had to act. So I did.

While still in high school, I wrote to politicians asking them to move climate legislation forward, organized my school’s participation in a climate strike, and taught my family to live more sustainably. Moving from secondary to tertiary education, my passion for climate activism only grew.

I’m not that special. I could be anybody, if we taught all students about climate change. The power of education has been clearly demonstrated, from achievements in gender equality to accelerations in economic growth. The same potential exists with regards to climate change.

If carbon emissions aren’t halved by 2030, a mere decade away, and brought to net-zero by 2050, food prices will rise, natural disasters will become more severe, and new widespread diseases will emerge — a potential effect now felt more acutely in the midst of a pandemic than ever before. In many ways, these effects and others are already playing out. Whether you think students should or shouldn’t leave school for a climate strike, or whether you think transitioning to renewable energy is a realistic goal or a fantasy, all of us can agree that a world of food shortages, destroyed homes, and pandemics isn’t one we want. As it turns out, us young people are the ones best able to prevent it.

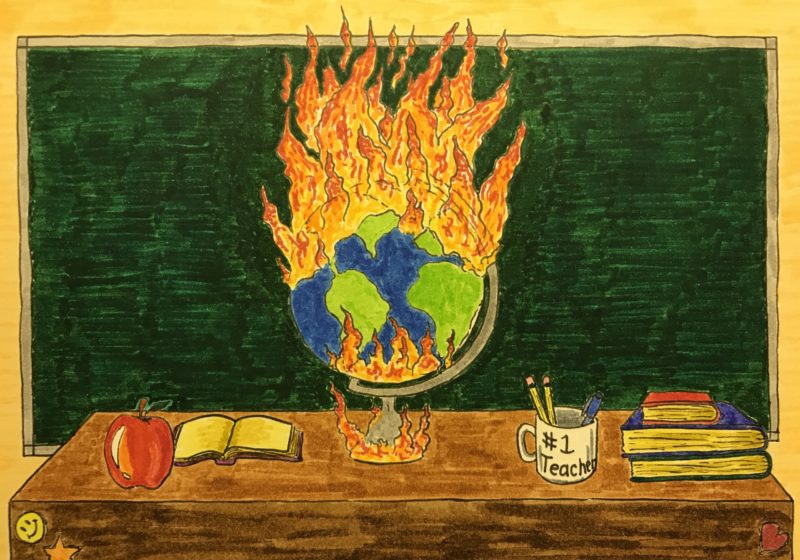

Neglecting to educate our youth about their very real future fails them. Their world is the one at risk, and when we as a society don’t tell them about it, we steal the voices most relevant to this conversation. In so doing, we cripple youths’ ability to secure their own futures.

Well-intentioned parents and educators may consider it more important that their child focus on a high GPA, learn to pass standardized tests, and get into college than act on climate change. Climate action, though, is now just as pressing — if not more so — on students’ futures than SAT prep. If we wouldn’t send our students to college unprepared, we cannot send them into the climate crisis unprepared either.

As youth are the most impacted and impactful when it comes to climate change, we do them the greatest of disservices by withholding relevant and crucial education. When parents speak to their children and schools to their students, the potential for change and reasons for hope only grow, and life for all future generations looks brighter. If we’re to make use of the critical window we have to mitigate the effects of climate change, we must begin by teaching our students, the earlier the better, about the climate crisis and their role in it.