NASA’s Perseverance rover found something remarkable on Mars last year: organic carbon in close proximity to a rock with unexpected clusters of minerals that, on Earth, form around decaying matter.

The headlines exploded, declaring that NASA found proof of life on Mars. This, however, is not quite accurate. What NASA actually found was a potential biosignature. Not life, not proof; but potential. That word matters. This Mars discovery, and the media reaction to it, highlights the importance of slowing down and reading beyond the headlines, and why budget cuts to NASA threaten our ability to answer the most profound question we have ever asked.

In July 2024, Perseverance drilled into a rock in Jezero Crater on Mars. Jezero was chosen for landing because its topography shows the presence of channels potentially cut by long-dried Martian rivers. NASA took a core sample, codenamed Sapphire Canyon, from a larger rock, codenamed Cheyava Falls, from a sedimentary rock formation within Jezero called Bright Angel (NASA loves its nicknames).

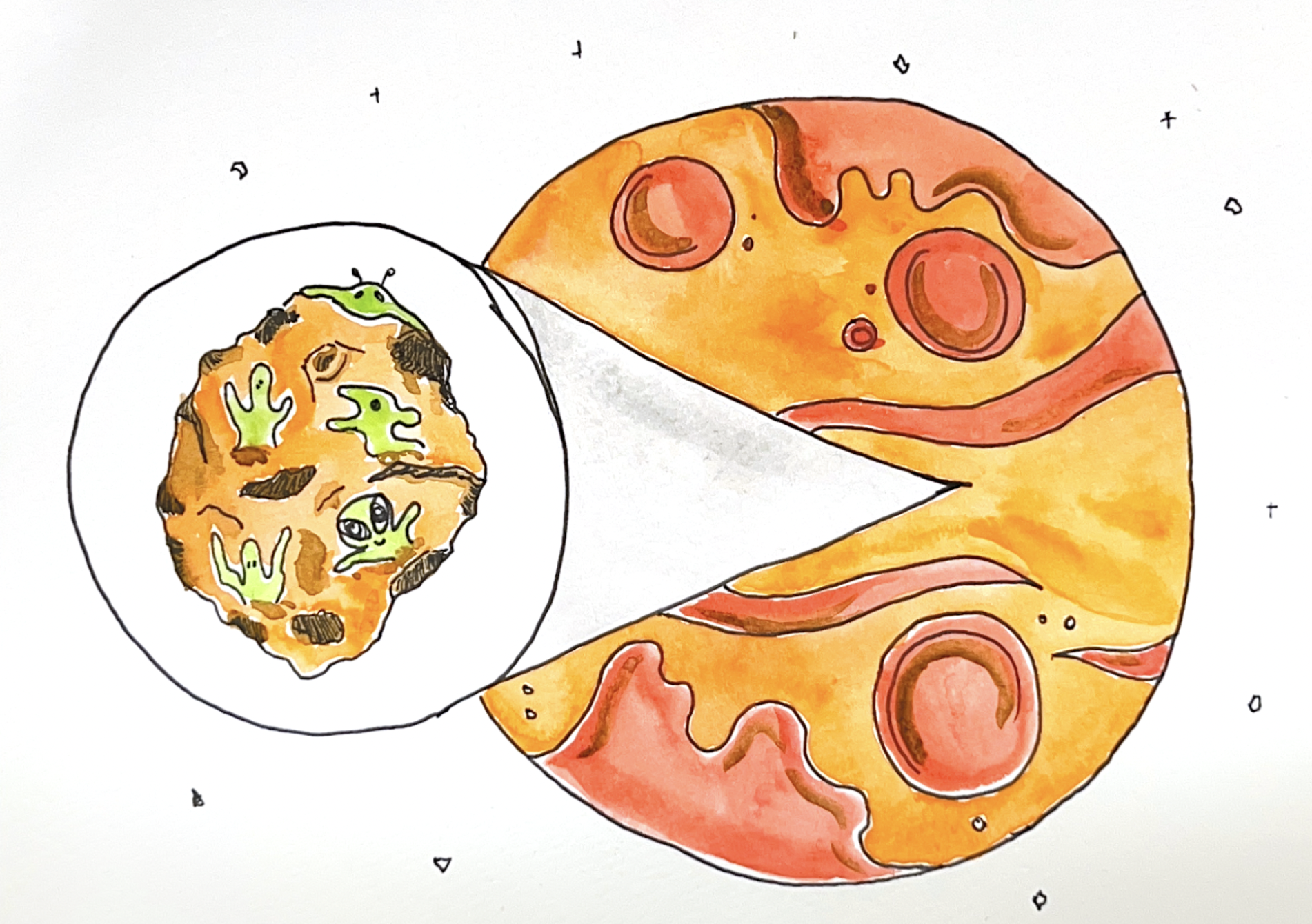

The team found tiny round features called “leopard spots” distributed randomly across the surface of the sample. The rims of the spots have the chemical signatures for two minerals: an iron phosphide called vivianite and an iron sulfide called greigite… The Bright Angel formation was previously discovered to contain organic carbon and is composed of fine-grained silt and clay, materials known on earth to preserve organic matter.

On Earth, vivianite and greigite are commonly found near decaying organic matter in wet, low-oxygen environments. Microbes can help produce them, and the evidence suggests the reactions that produced these minerals occurred at a relatively low, life-friendly temperature. This is what got people excited. Unfortunately, these minerals can also result from inorganic reactions — no life required.

The research team spent over a year carefully analyzing the data before publishing their findings in Nature in September 2025, where they lay out both the biotic and abiotic (meaning with and without the presence of life) explanations for the presence of the potential life signature. On Earth, these “leopard spots” can form through sustained high heat, acidic fluids, or binding by certain organic compounds that are not of biological origin. However, the Bright Angel rocks do not show signs of high heat or strong acid, making the two non-life routes less likely. The team cannot yet rule out all non-life routes, which is why they say “potential,” not “proof.”

The rock itself adds to the case for a true biosignature. It consists of fine-grained mudstone, silt, and clay. On Earth, mud can effectively trap tiny textures and chemical traces, making this kind of rock really good at preserving valuable scientific evidence. Organic carbon, sulfur, phosphorus, and iron were found in the Mars rock, which are essential ingredients for life. But this is not a surefire sign of life either — organic carbon is vital to life on Earth, but its presence can still be explained through abiotic processes.

Some headlines got it right: “Perseverance found possible biosignatures” and “Potential biosignature discovered,” some publications wrote. Others rushed past the nuance: “Clearest sign of life,” or, “Groundbreaking discovery of life on Mars,” they said. This second group is wrong. This is not proof of life; it is the most interesting potential biosignature we have found. There is a difference.

When headlines oversell the science, people stop trusting scientists. The findings are exciting, but the more pertinent problem is what comes next, or what does not come next. To tell life from non-life, we need the Sapphire Canyon core sample in an Earth lab. The rover’s tools are good, but not good enough. Katie Stack Morgan, deputy project scientist for the mission, puts it plainly: “We are pretty close to the limits of what the rover can do.” The rover’s X-ray tool (PIXL) and laser analysis tool (SHERLOC) told us where these minerals are, but only Earth labs can tell us how they formed. And that’s where Mars Sample Return (MSR) comes in, which is responsible for flying these cores back to Earth for testing.

But MSR is dying. The Trump administration proposed canceling it entirely in May 2025, the justification being that sample return “will be achieved by human missions to Mars.”Congress quickly pushed back and both the House and Senate rejected the cuts, the program remains in limbo as the cuts also removed NASA’s administrator and no replacement was made. The program that would answer whether we found life on Mars is stuck in political gridlock.

Why does this matter? Some argue that the MSR costs too much. Indeed, the program’s budget did balloon from $5.3 billion to $11 billion. However, compare it to what we would gain: a chance to investigate whether life exists beyond Earth, knowledge to shape future Mars missions, and the inspiration for a generation of scientists. We have spent two decades and billions of dollars building Perseverance and training it to find exactly this kind of sample, and we found it. Leaving it there now is not fiscal responsibility, it’s pure waste. The cost of not knowing is higher.

The hunt for life is worth perseverance. We can wait a few years for a clean answer, and we should pay for the final step that makes the answer real. Headlines can shout today, and the rocks will still be there tomorrow. Call your representatives. Tell them to fund the MSR. This is not about abstract science — it is about answering a question humans have asked for millennia: Are we alone?