The week of Feb. 23 was marked by a festival dedicated to the music of visiting composer Krzysztof Penderecki. The events included a chamber music concert, an orchestra concert, a master class with student composers and a symposium hosted by the Eastman composition department. The evening chamber music concert on Feb. 24 in Kilbourn Hall featured pieces written over the span of almost 50 years. First, Oleh Krysa and Tatiana Tchekina performed the “Sonata for Violin and Piano,” composed in 1953. This 10 minute work is structured as a classical sonata. The careful formal design foreshadows Penderecki’s success in writing large-scale forms. The three “Miniatures for Violin and Piano” would have sounded incredibly adventurous back in 1959 when they were written. After George Taylor’s somewhat slow performance of the “Cadenza for Solo Viola,” the first half closed with the “Quartet for Clarinet and String trio,” written in 1993. The second half of the concert consisted of one work only – “Sextet for Piano, Violin,Viola, Cello, Clarinet and French Horn,” written in 2000. It consists of two contrasting movements. The second, slow movement featured several romantic cello solos, performed with great musicality by Steven Doane. Pianist Dmitri Alexeev deserves special congratulations as well. The “Sextet” was an amazing success both for the composer and for the performers. It warranted a spontaneous standing ovation for Penderecki and the audience refused to leave until the ensemble repeated the fast movement. The Tuesday afternoon master class, as well as the Thursday symposium, was open to the public. Eastman composers presented their work to Penderecki. He did not make any constructive comments or suggestions – instead, he only congratulated each of the composers for their good work. It appeared as though he was afraid of offending them. “I don’t think composition can be taught,” he said. “This is why I quit teaching long ago. Everyone has to find his own voice. Back in the ’60s there was a Polish school, but now it is like here. Everyone writes different music,” he said. His last comment was a compliment to everyone present. “This is one of your best music schools. You are lucky to be here,” he said.The symposium on Thursday was even more illuminating on Penderecki’s personality. He spoke slowly, but in correct English. He talked in a very straightforward and honest manner about his music by warning everyone present, “Don’t believe when the artist talks about his own work. You have to believe what you listen to.” Asked about how his style from the ’60s relates to his contemporary work, he replied, “You know, everybody always asks me about the ’60s. What we did back then took five years, six years at the most. Avant-garde is the past now. There are some important pieces left, maybe twenty. You know which ones they are. We live in a different time now. Stravinsky didn’t write ‘Petrushka’ once more. He changed over time. No one can write more progressive string writing then I did in the ‘Threnody.’ I know I can’t. I left avant-garde, but I didn’t leave music.” Penderecki used sad humor when referring to the place of new music in today’s concert life. “In the so-called normal concert in Europe you hear again and again the same pieces. I see here is the same.” He mentioned several times that he is not afraid to be influenced. “‘My Passion’ has influences from 16th-century polyphony. You don’t hear it, but it is there.” He played parts of his work ‘Seven Days of Jerusalem,’ commissioned for the 3,000th anniversary of the city of Jerusalem. The nature of the composition invited questions about the composer’s religious music and affiliation. “My grandfather was Greek Orthodox. My grandmother was Armenian. I was writing in the Orthodox tradition. I proably heard church music first. I have Catholic heritage, too,” he said.The symposium with the famous composer was an informal and very relaxed meeting. Penderecki replied to all questions in depth and with good humor. He was very friendly and willing to converse with everyone even after the official ending of the symposium. The concert of the Eastman Philharmonia was the closing event of the weeklong festival. Brad Lubman conducted the first half, which constituted of “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima,” “De natura sonoris No. 1” and “Dream of Jacob.” Penderecki himself conducted his “Violin Concerto No. 2,” with Krysa performing the solo. With the help of an extra rehearsal, the Eastman undergraduates delivered a very convincing performance of all three pieces of the first half. The cleanly alternating sound blocks of “De sonoris” and the blending ocarina ensemble of the “Dream” both showed the high level of preparation and dedication from both conductor and orchestra. The “Violin concerto” sounded similar to all of Penderecki’s later music, which the Eastman community had the opportunity to hear live and on recordings this week. The melodies center around a falling chromatic motif. This music is very different from the avant-garde, which the composer pioneered forty years ago. However, the style and personality of the great musician was evident in every work. “Write the music that you want to hear,” Penderecki said, “and don’t be afraid.” Fol can be reached at afol@campustimes.org.

calendwatch

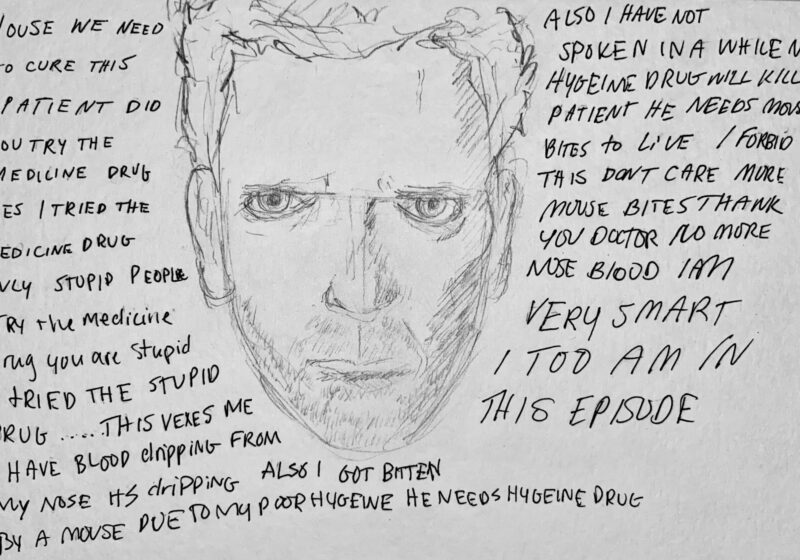

Housepital-ity

I fear I may have started this job off on the wrong foot. Right off the bat, when I stumbled into the reception of URMC, I committed the critical silly of asking where to go.

Center for Community Engagement

Fighting against poverty in Rochester with the Urban Fellows Program

Urban Fellows, an annual program hosted by the Center for Community Engagement (CCE) and funded by Americorp, gives undergraduate students the opportunity to work with local nonprofits over the summer — and get paid for it.

Class Council

Students’ Association releases Fall 2024 election results

With new additions to the 2028 Class Council and Senate, UR’s Students Association has welcomed new members as a result of the Fall 2024 Elections.