In July 1964, three days of social unrest broke out in Rochester. While the events were characterized by the media as shocking and out of the blue, many directly involved felt them to be the culmination of years of racism in policy and policing. In the second of our three-part series on the uprisings and their implications, we explore the role of housing in setting the stage for what some deemed riots, others uprisings. Read the first article here.

When army vet and lawyer Reuben Davis moved to Rochester in 1955, he was hopeful about the prospect of success in a city known for its economic prosperity.

But it soon became apparent to Davis that as a Black man, he was not included in the comforts of the city’s industrial opportunities.

When Davis and his wife set off to find a house, their favorite was on Elmdorf Ave in the 19th Ward. “The owner refused to sell to us because we were Black,” Davis recalled in an interview for the Rochester Voices project. The deed for the house itself mandated that it wasn’t to be sold to “coloreds and Italians,” Davis said. This was despite the fact that such restrictive deeds were outlawed by 1958 when they attempted to buy the house.

An active member of the NAACP, Davis had learned to navigate racist restrictions, and was able to get a white friend to buy the house and transfer its ownership to him.

This was a familiar story for many Black Rochesterians, who also discovered the hard way that Rochester’s version of the American Dream wasn’t for them, regardless of their educational or economic status. Decades of testimonials and research have explored Rochester’s long-standing history of racist housing policies and practices.

“The housing situation always has been an enigma to [Black people],” Reverend Charles Boddie said in a January 1946 Democrat & Chronicle article, adding that, “[i]n Rochester only two areas have been gracefully made available to [them].”

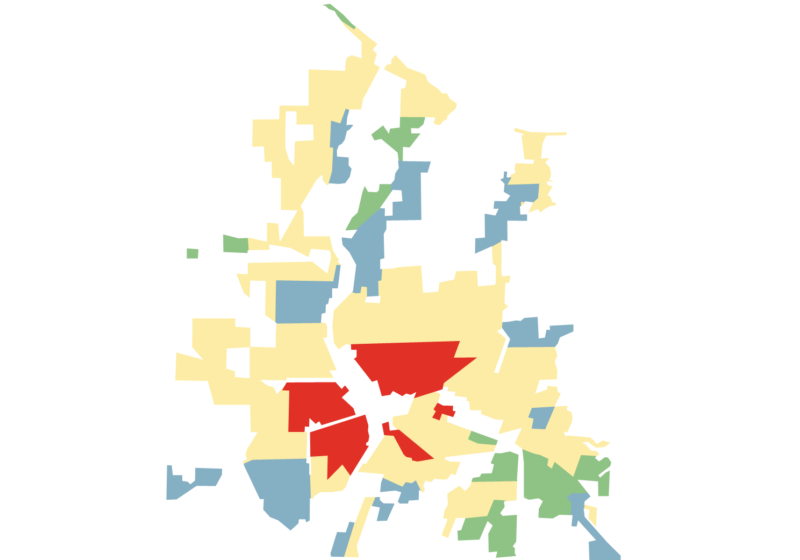

The Third and Seventh wards were home to 80 percent of Black Rochesterians in 1950, according to a 1958 NYS Commission Against Discrimination report.

The report detailed that 19.4% of houses in these two wards had no usable private bathrooms, 27.5% had no clean running water, and 12% had more than one person per bedroom.

Despite the poor conditions, “[i]f any attempt is made to move out of the [Third and Seventh wards], the attempt is met with opposition,” Rochester reverend Arthur Whitaker said in the documentary “July ‘64.”

Indeed, the 1958 report identifies Rochester as among the cities where a family of color moving into an otherwise white neighborhood would be met with resounding resistance. This often took the form of verbal insults, social ostracism, destruction of property, and in the case of Rochestarians Alice and James Young, written threats from the Ku Klux Klan.

Like Davis, the Youngs struggled to buy their own home, even though they could afford it, because the paperwork for their prospective home came with clauses prohibiting their purchase on the basis of race.

These racist legal contracts, often called restrictive covenants, explicitly banned people of a certain race or ethnicity from purchasing certain properties. Covenants like these were pushed and employed by the real estate industry in the first half of the 20th century across the United States.

Restrictive covenants are something that Shane Wiegand, a fourth grade teacher in the Rush Henrietta School District, often discusses. Wiegand, also a board member for the City Roots Community Land Trust, frequently holds talks on the history of gentrification and racist policy in Rochester. The most recent was back in July, hosted by Fairport Deputy Mayor Matthew Brown over Zoom.

During that talk, titled “Racist Policy and Resistance in Rochester,” Wiegand made an important distinction in Rochester’s historically racist housing — de facto vs. de jure segregation.

Richard Rothstein, in his book “The Color of Law,” writes that segregation in America was not the natural, unintended consequence of individual prejudices and actions (de facto segregation), but rather the purposeful result of racist, exclusionary government policy (de jure segregation).

“Without our government’s purposeful imposition of racial segregation, the other causes [of segregation] — private prejudice, white flight, real estate steering, bank redlining, income differences, and self-segregation — still would have existed but with far less opportunity for expression,” Rothstein writes.

The 2020 report on restrictive covenants in Rochester by City Roots and the Yale Environmental Protection Clinic acknowledges that segregation in the Rochester area was a product of institutional white supremacy — “a system built specifically to increase the dignity, power, and wealth of white people by taking those things from Black and Brown people.”

The federal government propagated housing segregation through the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), organizations created during the New Deal policy era. The HOLC, created in 1933, was tasked with determining the creditworthiness of neighborhoods and grading them on a scale of “best” to “hazardous.”

If a neighborhood had minority communities, HOLC would lower its score, all but preventing investments from going into communities of color.

In 1939, HOLC appraisers assessed Rochester and designated large swaths of the predominantly Black Third and Seventh wards as “hazardous.” Their 1939 report insinuated Black people were responsible for the neighborhoods’ poverty levels, saying that Black people “have come to [a part of the Third Ward] and today it is the poorest section of the entire city.”

Explicitly racist policies directly from federal authorities were not an anomaly: The FHA’s 1936 manual dissuaged racial integration, stating that “if a neighborhood is to retain stability it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes.”

In his July talk to Fairport residents, Wiegand described how the 1939 edition of the FHA underwriting manual went so far as to “mandate that if you’re going to build a new suburban housing tract, in order to get the FHA to underwrite your material costs upfront, you must impose racial deed restrictions that prohibit the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended.”

Even seemingly innocuous community spaces like parks and roads were strategically placed with racial segregation in mind. The 1939 manual encouraged having “natural or artificially established barriers” put in place to separate “inharmonious racial groups.” As Wiegand explains, “that’s how we get something like 490 or the Inner Loop — separating white and Black neighborhoods in downtown Rochester.”

As a direct consequence of these policies, Black Rochesterians were denied from buying homes in already affluent areas like suburbs, because they were predominantly white, excluding Black people from one of the best ways to accumulate and retain wealth.

Not only was the federal government instrumental in creating a segregated, inequitable Rochester but the local government was, too.

A prime example is the displacement of the Baden-Ormond settlement residents. In 1959, an urban renewal project cleared 60 acres of the Seventh Ward settlement to build a new low-income housing development.

Six hundred families and 150 businesses were immediately displaced to make room for, among other things, a new housing development, Chatham Gardens. In September 1963, the Democrat & Chronicle reported that only 184 Chatham Gardens apartments had been built, a fraction of the housing necessary to accommodate the displaced families.

The development also had an integration standard requiring that the white-to-non-white resident ratio remain equal, even though the overwhelming majority of displaced residents weren’t white.In 1964, it was announced that the remaining acres would become home to a warehouse, a Pepsi-Cola bottling factory, and a UPS installation.

And with these housing disparities, health inequities followed.

Minister Franklin Florence, a Rochester civil rights leader and former president of civil rights group F.I.G.H.T., said in “July ‘64” that it was “just inhuman for human beings to be” in the homes Black people were forced to inhabit, calling it a shame to a society that calls itself civilized.

Wiegand cited some stats on this health crisis in his July lecture: Anthony L. Jordan, the second Black doctor in Rochester, found that Black Rochesterians were dying at rates 50 percent higher than white Rochesterians, and the tuberculosis death rate among Black people was two-and-a-half times that of white people. Both statistics were “directly linked to housing and forced segregation,” Wiegand said.

This barrage of injustices compounded over decades, finally exploding into the Rochester uprisings of July 1964.

In the words of a NYS Commission Against Discrimination report from the late 1950s, “Rochester today is sitting on a pressure cooker whose relief valve has long been choked.”

Carolyn Vacca, the chair of St. John Fisher College’s history department, found a statistical correlation between the percentage of a given neighborhood’s population who were arrested in the uprisings and that neighborhood’s housing conditions. In other words, the people who lived in the worst housing were the most likely to be in the streets those July nights.

As Eastman Kodak scientist and president of the Rochester branch of the NAACP Walter Cooper said, “The fact that the riots occurred with so few deaths indicated that the rage was directed at the symbols of the power of the white establishment and the property in the run-down [neighborhood], which the participants inhabited.”

So, despite the prevailing opinion among many white Rochesterians at the time, the so-called riots of 1964 were anything but a surprise — rather, an inevitable consequence of bubbling social discontent and inadequate access to a basic human right: shelter.

Special thanks to Shane Wiegand, whose invaluable materials and sources provided necessary context and many of the examples for this article.