At its March meeting, the University Board of Trustees raised tuition for the coming academic to $44,580, a 3.9 percent increase from last year.

Although touted as the lowest rate change in over a decade, the percent increase is about average, after adjusting for year-to-year inflation. The lowest rate, adjusted for inflation, was actually in 2009 when tuition rates for the coming year decreased by a tenth of a percent.

The yearly increases go towards a variety of things, notably faculty compensation, all aimed at improving the University.

“A very large percentage of the College budget is for personnel,” University President Joel Seligman explained in an interview.

“Sometimes we have to engage in compensation increases to attract and retain outstanding faculty, but the reality is over time, compensation for staff, for faculty, does not stand still.”

According to the “Chronicle of Higher Education,” UR full, associate, and assistant professors are paid well above the median salary, but our instructor and lecturer salaries are ranked at the 33rd percentile.

“[We’ve] got some great scholars who are working here, relative to peers elsewhere, at somewhat lower compensation,” Seligman said. “They’re doing it because they love their colleagues, they love Rochester.”

When asked if they saw the constantly increasing faculty compensation as a sort of “arms race,” both Seligman and Provost and

Dean of the Faculty of Arts, Sciences & Engineering Peter Lennie disagreed.

“We are very concerned that we have the very best faculty,” Lennie said. “We compete effectively for it when in fact our faculty salaries are lower in relation to many of the places we compete with. So we’re able to attract great faculty without having to pay a vast premium for it because we provide a good place for faculty to work. So it would be a mistake to suppose that our faculty is paid for through this arms race. It’s just not the way we view it at all.”

Seligman did recognize the free market dynamic and the necessity to compete for faculty.

“When you decide to teach at UR, you’re allowed to leave, as every individual is in this country,” he said. “So we have to prove not only to students we provide the best quality education we can and justify the tuition levels, but we also have to provide to faculty on a daily basis the most congenial colleagues [and] the greatest possible support so they’ll be comfortable staying here.”

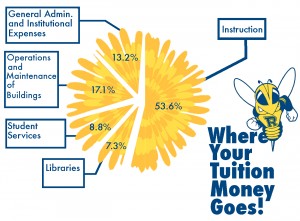

Besides salaries, tuition goes toward libraries, student services, operations and maintenance of buildings, and general administrative and institutional expenses.

“We want to offer the academic options and student life that we do, and tuition provides the means to pay for that,” Dean of the College of Arts, Sciences & Engineering Richard Feldman explained in a phone interview.

While important, tuition only covers about 60 percent of University expenses, leaving another 40 percent to be covered by drawing from invested endowment funds, government grants, and other miscellaneous sources.

“You have to recognize that tuition, while an immensely important contributor, doesn’t actually cover the whole cost of what we do,” Lennie said. “But by far the most important [source], though by no means all of it, comes from tuition.”

Although inflation-adjusted rates of tuition increase have risen since 2009, they’re at a lower average level than in the first half of the decade. Seligman attributed this decrease to lower inflation rates, lower comparative rates at peer institutions, and a less urgent need for rapid growth.

“In terms of the future, I wouldn’t assume that every year predicts what the next year will be,” Seligman said. “But I will say that we are in a period where [in] the foreseeable future, if inflation remains low, we are determined to be fiscally accountable.”

The process of budgeting and eventually raising tuition is not a simple matter. Seligman described a balance between four main things: the strategic needs of the school, the size of the endowment payout, the needs of the faculty, and the students’ ability to pay in comparison to peer institutions.

“Each year, for each school, we go through a [budgeting] process,” Seligman explained. “We’ll review it, and we’re always balancing the following types of considerations. But this didn’t happen in 10 minutes. This took a lot of work and buildup in the College to put together the budget. It’s not as if we have a check in the box kind of process.”

After budgeting, there was an extensive presentation to the Board of Trustees including the proposed budgets, the tuition recommendation, and comparisons to peer institutions.

The Board has a lengthy discussion on the topic which Seligman described to be at times “robust.” For this reason, and to not stifle conversation, the meeting records are not made public.

“To be candid, the balance between quality and accountability is one we work at what feels like night and day for months to get right,” he said.

Although it’s difficult to be fiscally accountable with a University budget the size of UR’s, Seligman asserted the Board’s ability to keep them so.

“They really do encourage us to be fiscally responsible,” he said. “It’s certainly something we do anyway, but we’ve taken it to heart, their determination.”

Although there is little direct student involvement in the process, Seligman and Feldman are conscious of their needs.

“Between the emails, between the town hall meetings, between other ways that we reach out, I think we have a fairly clear sense of what students want,” Seligman explained.

Feldman also meets frequently with Students’ Association representatives and, according to Seligman, essentially advocates on behalf of students based on those interactions and his work with other student life faculty.

“Obviously [students] want the lowest level of tuition and tuition increases,” Seligman said. “But they want quality programs. It’s the balancing of the two that’s the challenge.”

This decision will affect undergraduates in both the College of Arts and Sciences and the Eastman School of Music. Including room and board, total expenses are set to increase from $55,476 to $57,644.

Rises in tuition among the University’s graduate schools are as follows: $40,100 for the William E. Simon School of Business Administration, a 4 percent increase; $39,936 for the Margaret Warner School of Education, a 3.8 percent increase; and $46,500 for the School of Medicine and Dentistry, a 4 percent increase.

When asked about the option of “locked-in tuition,” where incoming freshmen are guaranteed a consistent rate of tuition at the start of their undergraduate career, the responses were varied. Feldman remarked that he has “not been part of discussions of that” and doesn’t have a well thought view about it. Seligman had a few more thoughts on the topic.

“I’ve thought about it a lot,” Seligman said. “And the challenge I have is we don’t have a locked-in rate of inflation. We don’t have a locked-in faculty. We can’t lock in the level of sponsored research. And because the variable can be very dynamic, I would be concerned if we committed to a locked-in system, we would ultimately threaten the quality of the University.”

Seligman also cited institutions like Cooper Union which didn’t charge tuition at all until lately when they were overcome by costs. Lennie agreed with Seligman.

Esce is a member of the class of 2015.