A recent New York Times article, “Why Science Majors Change Their Minds (It’s Just So Darn Hard),” reported that approximately 40 percent of college students intending to study science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM) either switch to other subjects or fail to complete a degree at all.

According to the article, this concern may affect the U.S.’s ability to be competitive in the modern world.

The issue now, it seems, has become how to remedy the situation.

UR is among the top research universities in the country and boasts some of the highest-ranking programs in STEM. For example, U.S. News & World Report ranked the Hajim School of Engineering and Applied Sciences among the top 50 engineering schools in the country.

But attrition in STEM still occurs here, perhaps due in part to how challenging the programs are.

Senior Brian Street entered UR planning to major in physics and mathematics, but he expects to graduate with a degree in classics.

“I started out as a physics and math major because I thoroughly enjoyed the subject material in high school,” he said. “I found it intriguing because it was a way to explain how the universe works and how to manipulate it through calculation.”

High school developed Street’s profound interest in physics and math, presenting the material in a way that allowed him to naturally understand the subject. College, on the other hand, did not foster his curiosity the same way.

“I stopped being a physics major because the coursework became much too demanding and thus rather boring,”he said. “Where I had once enjoyed solving physics problems and learning about how the forces of electromagnetism effected objects, the mathematics [that were used were] beyond what I had learned previously.”

Other students, like senior Mathias Ferber, a chemical engineering major, came to UR intending to study in STEM programs and will follow through with that plan.

Ferber explained that engineering allows him to connect how material he has learned relates to his surroundings and the modern world. He believes it has a nice monetary benefit as well.

“Chemical engineering also has the added plus of a nice salary, job security and the ability to enter a variety of different fields once I graduate,” he said.

Attrition in STEM has its benefits, though, according to Ronni Pavan, a professor in the department of economics, who discussed the issue in a Labor Economics class discussion.

Pavan explained that in thinking about attrition, it is more useful to understand what is wrong with the situation than to assume that it is bad. In Pavan’s opinion, attrition is wasteful when students fail to complete a college degree, but it is not necessarily wasteful if they just switch majors.

Pavan went on to explain that students who change degree paths are simply learning what they do and do not like while finding their place in the economy.

Street agreed with this view, saying that “the coursework is much more intriguing and enjoyable, while still rigorous in the development of language skills.”

As the New York Times article notes, politicians and educators are constantly worrying about the global competitiveness of the U.S. and about keeping the country from falling behind in STEM. Meanwhile, other nations’ educational systems mandate that students choose what they want to study before entering college.

For example, in Italy — Pavan’s home country — “students are forced to make a very important decision with very limited information about what they like,” Pavan said. He further noted, though, that changing majors is very costly.

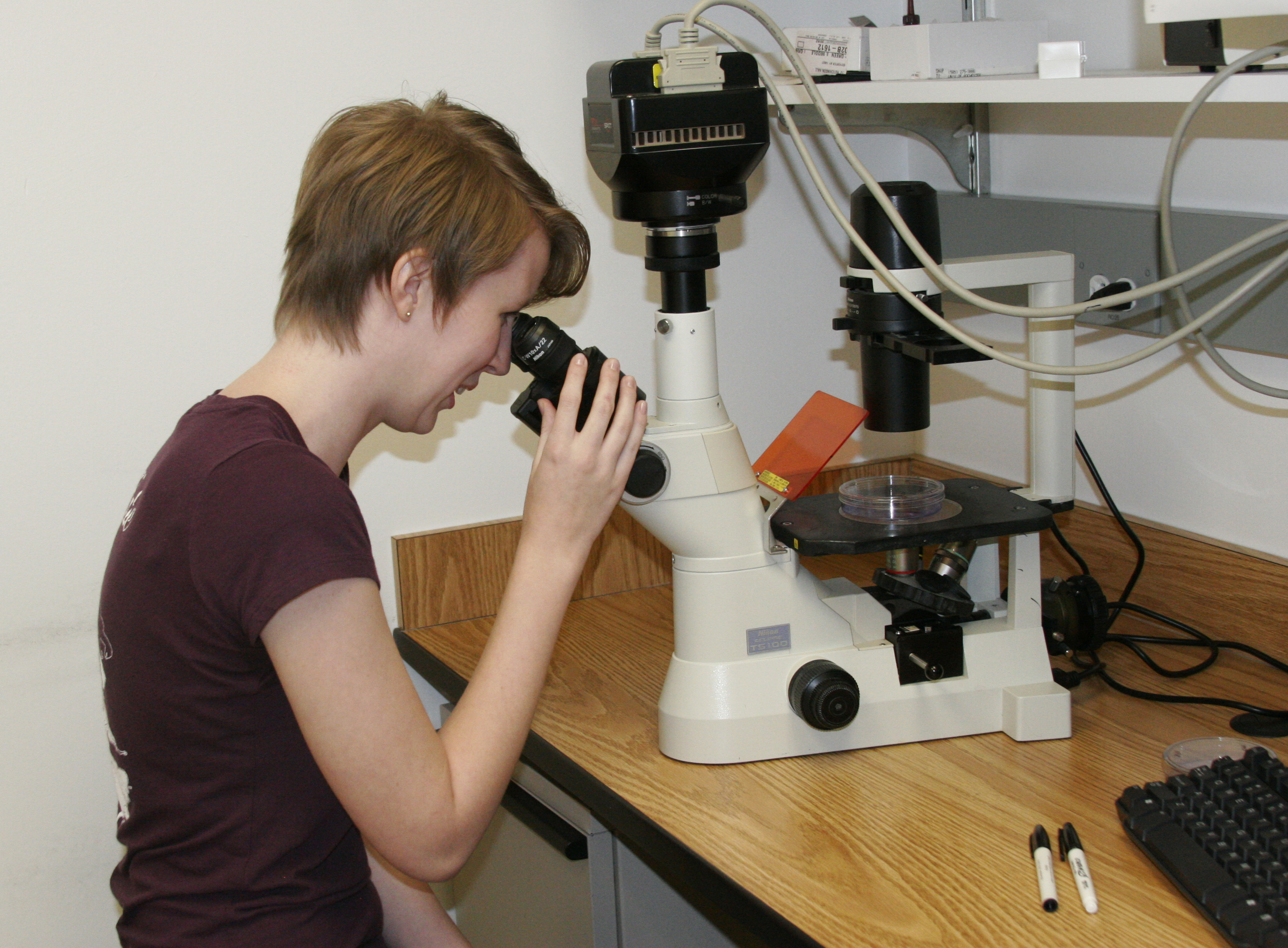

To allow students to figure out whether or not engineering is a student’s best fit, UR’s Hajim School of Engineering and Applied Sciences introduced its first series of introductory engineering courses last fall.

Robert Clark, Dean of Engineering and Applied Sciences, explained that the courses are mandatory for engineering majors but are open to students studying any field.

“These are all 100-level courses that are specifically introduced so that you don’t wait until junior year to get your first taste of what engineering is about,” Clark said. “We did feel we lost more students because they really had no tangible experience with engineering or an engineering course.”

Clark hopes these courses will help retain more students in engineering.

“It’s easier to climb the mountain in some ways if you know there’s an apex somewhere,” he said. “This is an opportunity to look at the apex early on, knowing that you’ve still got a good climb ahead. I hope it makes the ascent worthwhile.”

Seligman is a member of

the class of 2012.