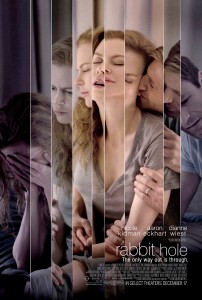

The poster for “Rabbit Hole” represents the many emotional stages that Becca (Kidman) and Howie (Eckhart) go through in the film. Courtesy of daemonstv.com

“Rabbit Hole” would be weak in any context, but it certainly didn’t help that a week before seeing it, I watched one of its award season competitors, “Blue Valentine.” That film, about a young couple’s love rescinding into sexual and psychological warfare, burns with true-life intensity. Even though we see the couple deteriorating before our eyes, and we feel the impact of every barbed dispute, the film never comes right out and shows exactly how the two leads went from an affectionate start to an embittered disaster. True to reality, the conflict raged with palpable emotions sometimes left unspoken.

“Rabbit Hole” has plenty of dramatic fervor, but it hardly has anything like nuance. We meet Becca (Nicole Kidman) and Howie (Aaron Eckhart), an upper-middle-class suburban couple that seems ordinary enough — but wait, there’s a major problem with these seemingly ordinary people! (For further reference, see: “Ordinary People.”) Their son, Danny, was recently killed when he chased the family dog into the street and was struck by a teenage motorist. The movie takes its sweet time in specifically disclosing Danny’s death, but the “subtle” approach feels false right from the beginning — there’s such a calculated effort to set up Becca and Howie’s apparent normality that you’d be surprised if they weren’t grieving the loss of a child.

But enjoy the calm façade while it lasts — once “Rabbit Hole” finally kicks into shattered family mode, it does so in full gear, leaving no emotion unscreamed for the remainder of the film. David Lindsay-Abaire wrote the original “Rabbit Hole” play, as well as the screenplay for this adaptation, but the drama awkwardly transitions from one format to the other. Almost any scene in the film’s rising action that pairs Becca and Howie turns into the kind of orderly, back-and-forth shouting match only actors have — come to think of it, I’m pretty sure every principle character gets yelled at by another one at some point. On stage, the anguished theatrics probably felt more natural. On screen, though, it’s just a tiring device. You’d think Becca and Howie are living next to the “Revolutionary Road” couple and have to yell over them.

Kidman and Eckhart are interesting casting choices for this film, for different reasons. Kidman, who snagged the film’s lone Oscar nomination for Best Actress, is about as convincing in the role as … well, as Nicole Kidman trying to seem like a grieving suburban housewife. Some will be won over by her performance (as the Academy clearly was), but, in my view, she’s one of those performers who’s just too big of a star to be convincing in a modestly-scaled role like this one.

Eckhart, meanwhile, has been completely overlooked, as is custom. He so rarely gets to play someone who’s inherently good at heart — his characters usually start off depraved or become depraved or are just depraved all the way through — so he really gets to shine in this fragile role. Eckhart excels at showing the thin line between Howie’s conflicted attitudes: he struggles so hard to seem cool and collected, but whenever that act slips, his volatility can be terrifying.

Either way, both characters work better in their separate plot arcs than paired together. Becca has an irresponsible and newly pregnant sister (Tammy Blanchard) and a mother dealing with a different kind of grief (Dianne Wiest). She also begins an odd, motherly acquaintance with her son’s killer, Jason (Miles Teller), an incredibly mild-mannered high school student who really just wants to start college, work on comic books and express that he’s sincerely, irrevocably distraught over what he did.

Howie, meanwhile, doesn’t seem to have much of a life until his wife stops attending group therapy with him, leaving him to enter into a flirtation with a fellow griever (Sandra Oh). When “Rabbit Hole” focuses on the characters’ private grief, rather than their showy disputes, the film finally feels like the delicate meditation it wants to be.

That especially comes through in the fantastic concluding scene, which offers a wise, and surprisingly quaint, wrap-up for the grueling emotions that precede it. Maybe “Rabbit Hole” itself could have used the same lesson its main characters learn: the sublime moments of progress are much more important than the emotional outbursts.

Grade: B-

Silverstein is a member of the class of 2013.